Math is everywhere.

-

Math is everywhere. Here's a tale where a bit of number theory let a couple of archeologists, Marion and Matthew Stirling, figure out that the Olmec civilization was incredibly old.

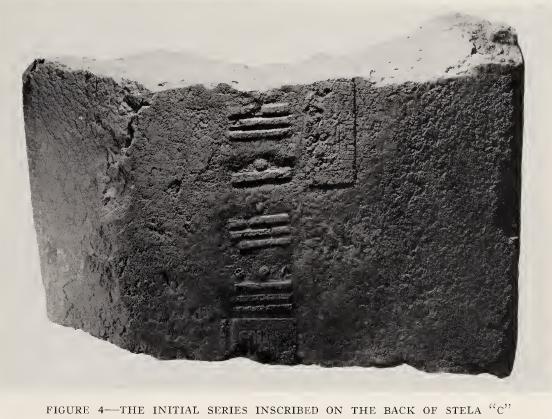

The Stirlings found the stone here in Mexico, and guessed that the date written on it was 7.16.6.16.18. In the calendar used by the Olmecs and other Central American civilizations, this corresponds to September 3, 32 BC.

But the first digit was missing from this part of the stone! All the Stirlings actually saw was 16.6.16.18. And the first digit was the most significant one! If it were 8 instead of 7, the date of the stone would be much later: roughly 362 AD, when the Mayans were in full swing.

The Stirlings guessed that the first digit must be 7 using a clever indirect argument.

The Olmecs and Mayans used two calendars! In addition to the calendar I just mentioned, called the Mesoamerican Long Count, they also used one called the Tzolkʼin. This uses a 260-day cycle, where each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And inscribed on this stone are not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count digits, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

This is what made the reconstruction possible!

(1/2)

-

Math is everywhere. Here's a tale where a bit of number theory let a couple of archeologists, Marion and Matthew Stirling, figure out that the Olmec civilization was incredibly old.

The Stirlings found the stone here in Mexico, and guessed that the date written on it was 7.16.6.16.18. In the calendar used by the Olmecs and other Central American civilizations, this corresponds to September 3, 32 BC.

But the first digit was missing from this part of the stone! All the Stirlings actually saw was 16.6.16.18. And the first digit was the most significant one! If it were 8 instead of 7, the date of the stone would be much later: roughly 362 AD, when the Mayans were in full swing.

The Stirlings guessed that the first digit must be 7 using a clever indirect argument.

The Olmecs and Mayans used two calendars! In addition to the calendar I just mentioned, called the Mesoamerican Long Count, they also used one called the Tzolkʼin. This uses a 260-day cycle, where each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And inscribed on this stone are not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count digits, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

This is what made the reconstruction possible!

(1/2)

The Meso-American Long Count identified any day by counting how many days passed since the world was created. This count is more or less in base 20, except that the second “digit” is in base 18, since they liked a year that was 18 × 20 = 360 years long. So,

7.16.6.16.18

would mean

7 × 144,000 + 16 × 7,200 + 6 × 360 + 16 × 20 + 18 = 1,125,698 days

after the world was created. But if the first digit was 8 instead of 7, the date would be 144,000 days later.

The Olmec's other calendar, the Tzolkʼin, uses a 260-day cycle. Here each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And the rock the Stirlings found had inscribed not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

Here’s why 7 was the only possible choice of the missing digit. Because the last four Long Count digits (16.6.16.18) are fixed, the total day count must be

B × 144,000 + 117,698.

for some B. But

144,000 = 0 mod 20,

and there are 20 different Tzolkʼin day names, so changing B by one doesn't change Tzolkʼin day name.

On the other hand, there are 13 different Tzolkʼin day numbers, so adding one to B adds

144,000 ≡ –1 (mod 13)

days to the Tzolkʼin day number. This means that after the day

7.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

the next day of the form

N.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

happens when N = 7+13. But this is 13 × 144,000 days later: that is, roughly 5,094 years after 32 BC! Far in the future!

So, while 32 BC seemed awfully early for the Olmecs to carve this stone, there’s no way they could have done it later. (Or earlier, for that matter.)

For a fuller story, read my blog article!

(2/2)

-

Math is everywhere. Here's a tale where a bit of number theory let a couple of archeologists, Marion and Matthew Stirling, figure out that the Olmec civilization was incredibly old.

The Stirlings found the stone here in Mexico, and guessed that the date written on it was 7.16.6.16.18. In the calendar used by the Olmecs and other Central American civilizations, this corresponds to September 3, 32 BC.

But the first digit was missing from this part of the stone! All the Stirlings actually saw was 16.6.16.18. And the first digit was the most significant one! If it were 8 instead of 7, the date of the stone would be much later: roughly 362 AD, when the Mayans were in full swing.

The Stirlings guessed that the first digit must be 7 using a clever indirect argument.

The Olmecs and Mayans used two calendars! In addition to the calendar I just mentioned, called the Mesoamerican Long Count, they also used one called the Tzolkʼin. This uses a 260-day cycle, where each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And inscribed on this stone are not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count digits, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

This is what made the reconstruction possible!

(1/2)

One Mayan inscription suggest that the Long Count was the truncation to the last 5 “digits” of an even longer count, and that a Long Count value such as 9.15.13.6.9 was in fact 13.13.13.13.13.13.13.13.9.15.13.6.9 in this Even Longer Count (why 13 everywhere? I don’t know!).

for some reason this makes me think of p-adic numbers. infinitely repeating 13s on the left side of the date, why not.

-

The Meso-American Long Count identified any day by counting how many days passed since the world was created. This count is more or less in base 20, except that the second “digit” is in base 18, since they liked a year that was 18 × 20 = 360 years long. So,

7.16.6.16.18

would mean

7 × 144,000 + 16 × 7,200 + 6 × 360 + 16 × 20 + 18 = 1,125,698 days

after the world was created. But if the first digit was 8 instead of 7, the date would be 144,000 days later.

The Olmec's other calendar, the Tzolkʼin, uses a 260-day cycle. Here each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And the rock the Stirlings found had inscribed not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

Here’s why 7 was the only possible choice of the missing digit. Because the last four Long Count digits (16.6.16.18) are fixed, the total day count must be

B × 144,000 + 117,698.

for some B. But

144,000 = 0 mod 20,

and there are 20 different Tzolkʼin day names, so changing B by one doesn't change Tzolkʼin day name.

On the other hand, there are 13 different Tzolkʼin day numbers, so adding one to B adds

144,000 ≡ –1 (mod 13)

days to the Tzolkʼin day number. This means that after the day

7.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

the next day of the form

N.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

happens when N = 7+13. But this is 13 × 144,000 days later: that is, roughly 5,094 years after 32 BC! Far in the future!

So, while 32 BC seemed awfully early for the Olmecs to carve this stone, there’s no way they could have done it later. (Or earlier, for that matter.)

For a fuller story, read my blog article!

(2/2)

@johncarlosbaez

> a year that was 18 × 20 = 360 years long"years" should be "days"

-

The Meso-American Long Count identified any day by counting how many days passed since the world was created. This count is more or less in base 20, except that the second “digit” is in base 18, since they liked a year that was 18 × 20 = 360 years long. So,

7.16.6.16.18

would mean

7 × 144,000 + 16 × 7,200 + 6 × 360 + 16 × 20 + 18 = 1,125,698 days

after the world was created. But if the first digit was 8 instead of 7, the date would be 144,000 days later.

The Olmec's other calendar, the Tzolkʼin, uses a 260-day cycle. Here each day gets its own number and name: there are 13 numbers and 20 names. And the rock the Stirlings found had inscribed not only the last four digits of the Mesoamerican Long Count, but also the Tzolkʼin day: 6 Etz’nab.

Here’s why 7 was the only possible choice of the missing digit. Because the last four Long Count digits (16.6.16.18) are fixed, the total day count must be

B × 144,000 + 117,698.

for some B. But

144,000 = 0 mod 20,

and there are 20 different Tzolkʼin day names, so changing B by one doesn't change Tzolkʼin day name.

On the other hand, there are 13 different Tzolkʼin day numbers, so adding one to B adds

144,000 ≡ –1 (mod 13)

days to the Tzolkʼin day number. This means that after the day

7.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

the next day of the form

N.16.6.16.18 and 6 Etz’nab

happens when N = 7+13. But this is 13 × 144,000 days later: that is, roughly 5,094 years after 32 BC! Far in the future!

So, while 32 BC seemed awfully early for the Olmecs to carve this stone, there’s no way they could have done it later. (Or earlier, for that matter.)

For a fuller story, read my blog article!

(2/2)

@johncarlosbaez

Thank you for sharing this

-

R ActivityRelay shared this topic