If you use AI-generated code, you currently cannot claim copyright on it in the US.

-

-

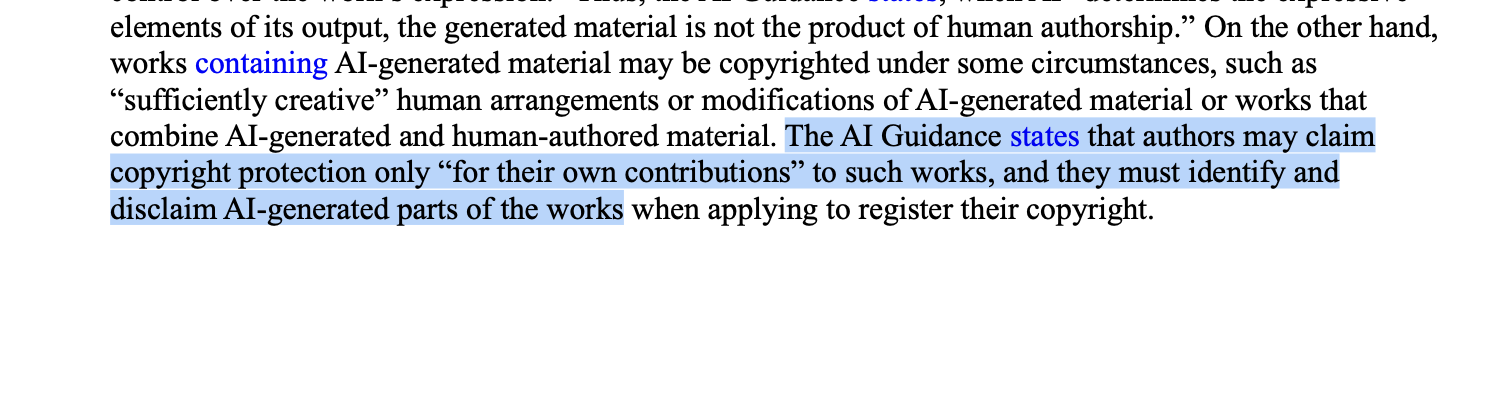

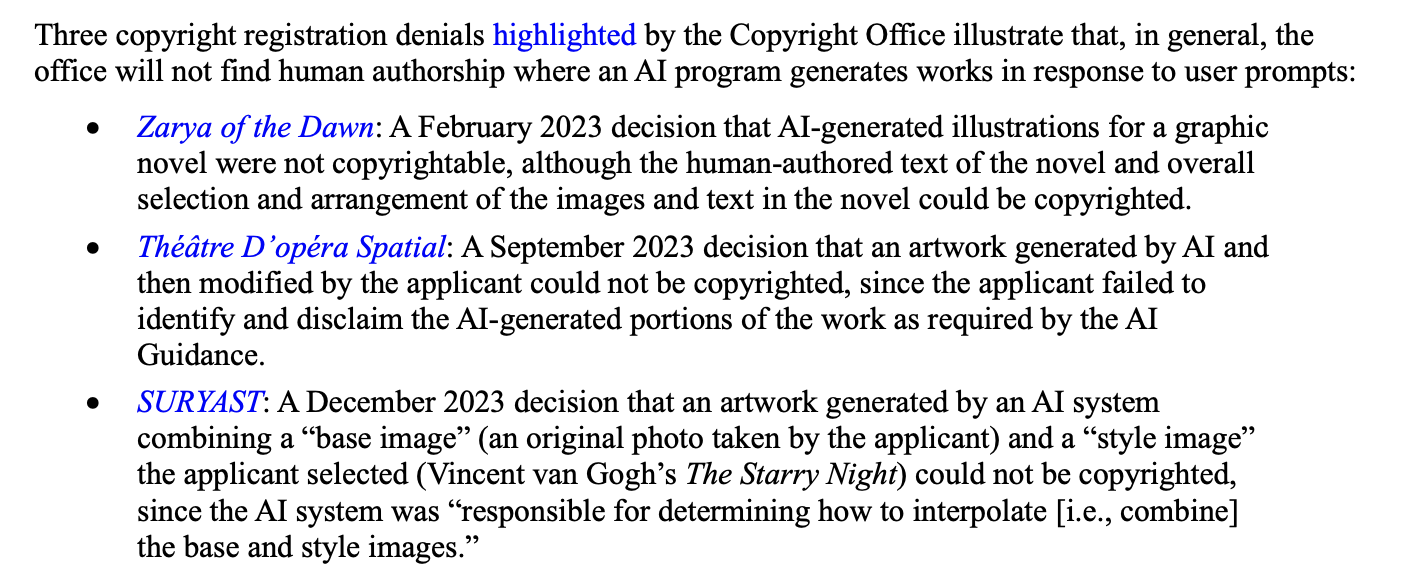

If you use AI-generated code, you currently cannot claim copyright on it in the US. If you fail to disclose/disclaim exactly which parts were not written by a human, you forfeit your copyright claim on *the entire codebase*.

This means copyright notices and even licenses folks are putting on their vibe-coded GitHub repos are unenforceable. The AI-generated code, and possibly the whole project, becomes public domain.

Source: https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/LSB/PDF/LSB10922/LSB10922.8.pdf

@jamie Just waiting for someone finding derivates of their own GPL code in propritary AI generated code...

-

If you use AI-generated code, you currently cannot claim copyright on it in the US. If you fail to disclose/disclaim exactly which parts were not written by a human, you forfeit your copyright claim on *the entire codebase*.

This means copyright notices and even licenses folks are putting on their vibe-coded GitHub repos are unenforceable. The AI-generated code, and possibly the whole project, becomes public domain.

Source: https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/LSB/PDF/LSB10922/LSB10922.8.pdf

@jamie so proprietary projects that are made with llms can be leaked legally since there's no copyright for it ?

-

@christianschwaegerl

maybe more like, sausages are vegan because an animal ate a vegan diet and then used those plant-based calories to grow it's animal body which was then packaged into a sausage.very vegan ; )

-

@fsinn @jamie My understanding was that training an AI model on copyrighted work was fair use, because the actual "distribution"--when the AI generates something from a prompt--uses a diminimus amount of copyrighted content from an individual work, except if the user explicitly prompted something like, "Give me Homer Simpson surfing a space orca," at which point the AI company would throw the user all the way under the bus.

-

@christianschwaegerl @jamie @Azuaron @fsinn

Yes. Any "direct quoting" of copyrighted works, as text files on a disk, for example, would > only be a bunch of numbers < too. ASCI, Unicode, UTF-8, etc. are ways of encoding text into numbers, and displaying text representations (glyphs) of them later.

So LLMs hold "indirect" and maybe "abstract" (or not) numbers related to the copyrighted works. Not sure how that will or should work out, from a legal perspective.

-

-

@katrinatransfem @fsinn @jamie If the material is acquired legally, they don't need a specific "license" to use it as training material. Copyright holders don't get to determine how their work is used after it's acquired, except to prevent its distribution.

Now, for the even larger than normal scumbags like Anthropic and Meta that torrented millions of books, that's certainly a problem. But Google, for instance, actually bought all the books they scanned.

@Azuaron @katrinatransfem @fsinn @jamie

I think that the careless, abusive, and harmful "gathering" practices need to be challenged as misuse of other's computing resources and the "distributed denial of service attacks" that they, in effect, are.

-

Additionally, AI generated code can be a copyright infringement if the AI basically generated a copy of some copyrighted code. And if we consider that AI is trained on lots of GPLed code there is a high probability it will generate code that would need to be licensed accordingly.

There is no clean room implementation of anything with AI. The code is immediately tainted.

@Lapizistik In the US, courts have determined (for now, at least) that training an AI model on copyrighted works is considered "fair use". So it's basically legalized copyright laundering. Even code released under the GPL loses its infectiousness when laundered through an LLM.

I'd be very interested to see what other countries do around that, because it would determine which models are legal to use where.

-

@Lapizistik In the US, courts have determined (for now, at least) that training an AI model on copyrighted works is considered "fair use". So it's basically legalized copyright laundering. Even code released under the GPL loses its infectiousness when laundered through an LLM.

I'd be very interested to see what other countries do around that, because it would determine which models are legal to use where.

@Lapizistik To be clear, I agree with you. It's a moral failure to make billions of dollars from other people's effort without compensating them at all.

-

@jamie A copyrighted work that isn't registered is still copyrighted. It's not "in the public domain."

Registration, in the U.S., allows for certain copyright enforcement actions that can't be taken for unregistered works. But whether or not a work is registered has no bearing on whether it is copyrighted vs. in the public domain.

(2/2)@jik In other parts of this thread, this is being discussed. I was limited on space, so I took shortcuts. What I meant is that, in order to enforce your copyright, you need to prove you own the copyright. Registering it is the single most effective way to do that.

If you can't register your copyright, you (effectively) can't enforce it.

If you can't enforce your copyright, your copyright vs public domain is a distinction without a meaningful difference.

I couldn't fit all that in the post.

-

@Lapizistik In the US, courts have determined (for now, at least) that training an AI model on copyrighted works is considered "fair use". So it's basically legalized copyright laundering. Even code released under the GPL loses its infectiousness when laundered through an LLM.

I'd be very interested to see what other countries do around that, because it would determine which models are legal to use where.

@jamie

This is not my point. Even if it _is_ “fair use”: if the llm produces a 1:1 copy (minus some renamed variables) of some relevant piece of code it is not producing something “new”. As a human I can learn from any code (copyrighted or not), but I cannot just take the code, rename some variables and publish it as my own creation. I would loose in court.¹So technically if you use an LLM to produce code for you you need to check if any relevant piece of it is a copy of anything that exists.

Clean room implementation requires the programmer to not have seen the original code but only the requirements.

__

¹otherwise you could just take any piece of copyrighted code, rename variables and say it is yours because an LLM has produced it. -

@christianschwaegerl @jamie @Azuaron @fsinn

Yes. Any "direct quoting" of copyrighted works, as text files on a disk, for example, would > only be a bunch of numbers < too. ASCI, Unicode, UTF-8, etc. are ways of encoding text into numbers, and displaying text representations (glyphs) of them later.

So LLMs hold "indirect" and maybe "abstract" (or not) numbers related to the copyrighted works. Not sure how that will or should work out, from a legal perspective.

@JeffGrigg @christianschwaegerl @jamie @fsinn I think this is missing the point and the law (at least, US copyright law).

I buy a book. I then own that book. I can cut that book into individual pages. I can scan all those pages into my computer. I can have an image-to-text algorithm convert the text in the images into an ebook. I can do this to a billion books. I can run whatever algorithms I want on the text of those books. I can store the resulting text of my algorithms on my computer, in any format.

This is all legal, for both me and for any company. Copyright does not prevent use of a work after it has been sold, "use" meaning just about anything--short of distributing the work.

Because what copyright protects against is the reproduction and distribution of copyrighted works. For AI companies, that "distribution" doesn't happen until somebody puts a prompt into the AI, and receives back a result. That result is the distribution. To sue an AI company for copyright infringement, you would have to have a result that infringes on your copyright, and you would have to prove that the AI company was more than just a tool that the prompter used to infringe your copyright.

For the Disney example, if somebody prompted, "Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel with Mickey Mouse," it would be an uphill battle to prove the AI company is responsible for that instead of just the prompter. The argument that the AI company would make is that the prompter clearly used the AI as a tool to make infringing work, but just like you can't sue Adobe if someone used Photoshop to make the same image, you can't sue the AI company because someone used it as a tool to infringe copyright.

Now, I don't find that a wholly persuasive argument because of the, frankly, complicity in the creation that AI has that Photoshop doesn't, but that's definitely the argument they would make, and judges have seemed receptive to that and similar (and even worse) arguments.

As far as I'm concerned, the original point of this thread proves that the AI company should be mostly-to-wholly responsible, even if the prompter was deliberately asking for infringing works. After all, AI-generated work is not copyrightable because it is not human created, it is computer created.

If it's not human created, how can the human be responsible for the infringement?

If it is computer created, then isn't the computer's owner responsible for the infringement?

After all, if I ask a digital artist to create me "Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel with Mickey Mouse," and they do, the digital artist is on the hook for that infringement. They reproduced the work, and they distributed it. There is a "prompter" and a "creator" in both scenarios; it seems illogical that if the "creator" is a human, they're responsible, but if the "creator" is a computer, they aren't responsible.

This is, per @pluralistic, "It's not a crime, I did it with an app!" Why we let apps get away with crimes we'd never tolerate from people, I don't know. But that's where we are.

-

@jamie @starr This was a big deal for authors in the Anthropic suit: those whose works had not been registered for whatever reason prior to the infringement were excluded from the settlement because they would only have been entitled to at most a few dollars in lost royalties, a fact-bound question not conducive to class action and for which they could not be awarded fees. (Foreign authors are understandably angry about this.)

@jamie @starr (The Berne Convention allows this because the formalities are only required to file suit, so it's no different under the convention from having to present any other form of documentary proof before a court. Copyright law in general was built on a centuries-old threat model of "infringer produces 10,000 copies of one work" and not "infringer produces one copy of 10,000 works" let alone the millions in various pirated e-book collections.)

-

@jik In other parts of this thread, this is being discussed. I was limited on space, so I took shortcuts. What I meant is that, in order to enforce your copyright, you need to prove you own the copyright. Registering it is the single most effective way to do that.

If you can't register your copyright, you (effectively) can't enforce it.

If you can't enforce your copyright, your copyright vs public domain is a distinction without a meaningful difference.

I couldn't fit all that in the post.

@jamie Right. You didn't have enough space. You couldn't have, oh, I dunno, posted correct information on multiple posts. You know, like the multiple posts on which you posted the incorrect information.

*plonk* -

@JeffGrigg @christianschwaegerl @jamie @fsinn I think this is missing the point and the law (at least, US copyright law).

I buy a book. I then own that book. I can cut that book into individual pages. I can scan all those pages into my computer. I can have an image-to-text algorithm convert the text in the images into an ebook. I can do this to a billion books. I can run whatever algorithms I want on the text of those books. I can store the resulting text of my algorithms on my computer, in any format.

This is all legal, for both me and for any company. Copyright does not prevent use of a work after it has been sold, "use" meaning just about anything--short of distributing the work.

Because what copyright protects against is the reproduction and distribution of copyrighted works. For AI companies, that "distribution" doesn't happen until somebody puts a prompt into the AI, and receives back a result. That result is the distribution. To sue an AI company for copyright infringement, you would have to have a result that infringes on your copyright, and you would have to prove that the AI company was more than just a tool that the prompter used to infringe your copyright.

For the Disney example, if somebody prompted, "Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel with Mickey Mouse," it would be an uphill battle to prove the AI company is responsible for that instead of just the prompter. The argument that the AI company would make is that the prompter clearly used the AI as a tool to make infringing work, but just like you can't sue Adobe if someone used Photoshop to make the same image, you can't sue the AI company because someone used it as a tool to infringe copyright.

Now, I don't find that a wholly persuasive argument because of the, frankly, complicity in the creation that AI has that Photoshop doesn't, but that's definitely the argument they would make, and judges have seemed receptive to that and similar (and even worse) arguments.

As far as I'm concerned, the original point of this thread proves that the AI company should be mostly-to-wholly responsible, even if the prompter was deliberately asking for infringing works. After all, AI-generated work is not copyrightable because it is not human created, it is computer created.

If it's not human created, how can the human be responsible for the infringement?

If it is computer created, then isn't the computer's owner responsible for the infringement?

After all, if I ask a digital artist to create me "Darth Vader in a lightsaber duel with Mickey Mouse," and they do, the digital artist is on the hook for that infringement. They reproduced the work, and they distributed it. There is a "prompter" and a "creator" in both scenarios; it seems illogical that if the "creator" is a human, they're responsible, but if the "creator" is a computer, they aren't responsible.

This is, per @pluralistic, "It's not a crime, I did it with an app!" Why we let apps get away with crimes we'd never tolerate from people, I don't know. But that's where we are.

@Azuaron @JeffGrigg @jamie @fsinn @pluralistic For a start, you bought the book. I doubt AI hyperscalers have met that minimum requirement. Secondly, you buy the book for your private use, not for commercial purposes. Thirdly, you describe reproduction for private purposes. Reproduce and sell, and you infringe. Fourth, you don’t use the book to instruct a machine to paraphrase the content, produce quotes and false quotes, and to write in the style of the author in an infinite number of cases.

-

If you use AI-generated code, you currently cannot claim copyright on it in the US. If you fail to disclose/disclaim exactly which parts were not written by a human, you forfeit your copyright claim on *the entire codebase*.

This means copyright notices and even licenses folks are putting on their vibe-coded GitHub repos are unenforceable. The AI-generated code, and possibly the whole project, becomes public domain.

Source: https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/LSB/PDF/LSB10922/LSB10922.8.pdf

"forfeit your copyright claim on *the entire codebase*" seems very unlikely since they're reissuing copyright on the human-authored parts of one of the works mentioned in your post:

> Because the current registration for the Work does not disclaim its Midjourney-generated content, we intend to cancel the original certificate issued to Ms. Kashtanova and issue a new one covering only the expressive material that she created.

-

@jamie @starr (The Berne Convention allows this because the formalities are only required to file suit, so it's no different under the convention from having to present any other form of documentary proof before a court. Copyright law in general was built on a centuries-old threat model of "infringer produces 10,000 copies of one work" and not "infringer produces one copy of 10,000 works" let alone the millions in various pirated e-book collections.)

@wollman @jamie this is all really interesting. Sounds like I misunderstood the importance of registering. I had thought that as long as you could prove that you had created a work, you were good. And I had recently read an article about someone tracking down a lost pilot for a sitcom to the LOC where they were able to watch it, so I had assumed that was how it generally worked.

-

@wollman @jamie this is all really interesting. Sounds like I misunderstood the importance of registering. I had thought that as long as you could prove that you had created a work, you were good. And I had recently read an article about someone tracking down a lost pilot for a sitcom to the LOC where they were able to watch it, so I had assumed that was how it generally worked.

@starr @jamie Audiovisual works being relatively easy to display in the library and also a part of the national cultural heritage, the LOC does tend to require deposit, but it's up to the librarians to decide whether they will add a copy to the nation's collection. I should read up on what they do for computer games, where the "work as a whole" may not even exist in one place or be in any way functional offline.

-

@Azuaron @JeffGrigg @jamie @fsinn @pluralistic For a start, you bought the book. I doubt AI hyperscalers have met that minimum requirement. Secondly, you buy the book for your private use, not for commercial purposes. Thirdly, you describe reproduction for private purposes. Reproduce and sell, and you infringe. Fourth, you don’t use the book to instruct a machine to paraphrase the content, produce quotes and false quotes, and to write in the style of the author in an infinite number of cases.

@christianschwaegerl @JeffGrigg @jamie @fsinn @pluralistic You're making a bunch of different arguments now. The topic at hand was, "Is it copyright infringement to make and have an AI model trained on millions of books?" The answer is no. This is wholly legal.

Storing copyrighted work is legal.

Modifying copyrighted work is legal.

Storing modified copyrighted work is legal.

It doesn't matter if they have a model that is literally just plain text of every book, or if the model is a series of mathematical weights that go into an algorithm. It's already legal to have and modify copyrighted works.

What becomes illegal is reproducing and distributing copyrighted material.

No, whether it was for "commercial" or "non-commercial" purposes doesn't matter when determining if something is infringing.

No, whether it was "sold" or "distributed for free" doesn't matter when determining if something is infringing.

"What about Fair Use?" Fair use is an affirmative defense. That means that you acknowledge you are infringing, but it's an allowed type of infringement. It's still an infringement, you just don't get punished for it.

But, as already stated, nothing is infringement until there's a distribution. Without a distribution, no further analysis is needed. When a distribution occurs, it is the distribution that is analyzed to determine if it is infringing, and, if so, if there is a fair use defense. Everything that happens prior to the distribution is irrelevant when determining if an infringement has occurred, as long as the accused infringer acknowledges they have the copyrighted work (which AI companies always acknowledge).

There is one further step, because it is illegal to make a tool that is for copyright infringement. The barrier to prove this is so high, though. As long as a tool has any non-infringing uses--and we must acknowledge AI can generate non-infringing responses--then it won't be nailed with being a "tool for copyright infringement". This has to be, like, "Hey, I made a cracker for DRM, it can only be used to crack DRM. It literally can't do anything legal."

Even video game emulators haven't been hit with being "tools for copyright infringement" because there are legitimate uses for them (personal backup, archival, etc.), even though everyone knows they're 99% for infringement.